Shein and the Tech Cold War

Algorithmic tweaks and clothing as trash

Ranjan here, it’s been a while and Can and I miss you! This week I’ll be writing about Shein, its relationship to TikTok, and the US-China tech cold war.

I’m sure most Margins readers have heard of the Chinese ecommerce juggernaut Shein (I’d be more curious how many have actually shopped on the site). For the uninitiated, Shein is a Chinese ecommerce site that receives accolades like being the “world’s largest online retailer” and the “3rd most valuable private company”. It clocked an estimated $16 billion in revenue in 2021 (for reference, H&M is ~$25bn and Zara is ~$28bn), and what’s more notable is its growth. Shein’s revenue was up 250% to $10 billion in 2020, and another 60% to $16 billion in 2021. Yes, they certainly benefited from the whole “10 years in 3 months” ecommerce acceleration during the height of the pandemic, but going from very solid online retailer to absolute global juggernaut is worth us exploring a bit more.

Shein Haul

In early 2020 I learned about the idea of a #ShenHaul and started following the rising TikTok trend of (mostly) younger consumers making a show of dumping out a big box of clothing and bragging about how much random stuff they got for the price.

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

I enjoyed the absurd juxtaposition of always reading how consumers want to be more sustainable (Note 1), while watching these consumers celebrate clothing as essentially trash. However, I was much more intrigued by how Shein sold clothes that cheaply.

Learning More

There was barely any info out there in early 2020, and it kind of felt like the early 2010s when I was desperate to learn more about Bytedance and Toutiao (more on this later). Shein was and continues to be a mystery. The founder was apparently an SEO marketing specialist who started a wedding dress company in 2011 called SheInside 🤢🤢. The company was renamed Shein in 2015 (Note 2).

By mid-2020, as the pandemic grew, I heard more and more about people purchasing off the site, but the only press coverage remained mini-controversies like swastika necklaces or decorative Muslim prayer rugs. There was still zero business coverage (this Oct 2020 reuters piece is the earliest I have in my readwise), but a lot of people within ecommerce and tech started talking about the company more, and the pesky TikTok algorithm kept feeding me more #sheinhauls.

By early 2021, Lil Nas X and Katy Perry promoted the brand and Shein was dominating social media globally. Packy McCormick’s The TikTok of Ecommerce was one of the first comprehensive pieces I read on the company. He has a section titled Why You’ve Never Heard of Shein where he outlines how meticulous the company was about hiding its country of origin:

Shein describes itself as an “international B2C fast fashion e-commerce platform” with business in more than 220 countries and regions around the world. Nothing Matthew could find on their official website, app or social media accounts references the company’s Chinese origins. In fact, the company is so serious about hiding its Chinese roots that it voluntarily claimed to be from New Jersey. Previously, the About page of Shein’s official website said the company began as “a small group of passionate fashion loving individuals in North Brunswick, New Jersey.” This has since been removed.

Shein’s otherwise detailed shipping status updates use generic terms such as “source country” and “port of departure,” avoiding reference to Guangzhou or Hong Kong. The company’s logo, branding and products are indistinguishable in their professionalism and quality from global industry peers.

Thus far, it’s worked. American politicians and media have been asleep at the wheel. It’s missing from apparel brand rankings . Run a search for “Shein” on the New York Times site--nothing. Wall Street Journal--nothing. But Shein’s still running ads against those searches.

He also started to answer that question of how they make the clothes so cheaply - introducing the concept of “real-time fashion” as a modern successor to fast-fashion (Note 3). What Zara and H&M did in the 1990s, Shein was doing in the 2020s.

There’s a vivid picture painted of how Shein leverages an increasing amount of preference and purchase data to make small batches of items to test, and rapidly scale up winners. They supposedly digitized hundreds of factories with their proprietary supply-chain management software to build an integrated testing-and-scaling manufacturing and commerce powerhouse.

They also started raising a lot of money. In 2015, they raised a $50mm Series B, which jumped to a 500mm Series D in 2019 from Tiger and Sequoia China (I couldn’t find anything on the amount of their Series C).

That funding exploded, alongside their growth, through the pandemic, and the whole business world heard of Shein after their massive April 2022 $1.5bn round that valued the company at $100bn.

In some ways this all seems reasonable. You have a company that, over many years, innovated in a somewhat antiquated sector (Chinese manufacturing) to create a new way of doing things (inventory management and apparel production) to deliver a cheaper, faster product. They spent years perfecting this while growing steadily, and then when the pandemic hit and they were perfectly positioned. It also dovetails perfectly with my favorite topic of the explosion of late-stage private funding.

But there’s still so much of it that remains a mystery to me, and it’s not just me. It seems every piece on the company references it as an enigma, or mysterious, or secretive, or some variant of that famous Churchill riddle wrapped in an engima quote.

And when a mysterious, secretive, enigmatic company upends decades-old incumbents to become a global category leader in the span of a few years, there’s got to be more to the story, right?

Cross-Border Arbitrage

The real-time fashion, supply chain revolution explanation is a good start, but this June 2021 Bloomberg piece puts more of the pieces together. It references and reinforces the idea of real-time fashion as an enabler, but introduces a fascinating new element: Trump’s Trade War. Because Shein sells directly to the American consumer, and virtually all individual orders are less than $800, it was already exempt from paying any duties. The piece details how, in 2018, as Trump launched his tariffs, China waived its export taxes for domestic direct-to-consumer companies in retaliation, and Shein, along with other Chinese ecommerce companies that sold DTC, found themselves in the enviable competitive position of not paying import or export taxes. In the most Trumpian of ironies, his actions helped spark a 67% increase in Chinese online retail exports in 2018.

Between supply chain innovation and the tax loopholes, it makes a lot of sense how they could undercut everyone on price. But what about the growth? How did they convince millions of American consumers to overcome the age-old reticence of buying “cheap Chinese” stuff to celebrating boxes full of cheap Chinese stuff.

Enter TikTok

Another Chinese tech giant that exploded in the past few years is TikTok. As TikTok, fueled by billions in acquisition ad spending, skyrocketed its influence on the global population, Shein became a master of the platform to generate its own growth. Right now the hashtag #shein has 39.7 billion views and #sheinhaul has 6.7 billion views. You see headlines like **TikTok Fashion Favorite Shein Considers a Big Step or **Shein's success through TikTok's hauls.

I don’t think we should separate these two things.

To caveat, Shein was early and masterful in influencer marketing, and the company has built a vast presence on other channels like Instagram and Youtube. Packy’s piece points out:

Shein was one of the first apparel companies to use social media influencers as early as 2011. They were one of the first early adopters of Pinterest, which became their top source of traffic during 2013-2014. Even more recently, Shein was early to TikTok marketing, becoming the most talked about brand on TikTok in 2020.

You have a brand that was well positioned to dominate in the influencer space, that perfectly captured the TikTok algorithm to mysteriously become as big as multi-decade retailers in a few years.

Two companies, perfectly poised for global domination. TikTok’s short-form video and contextual algorithm coupled with Shein’s revolutionary manufacturing prowess and influencer know-how. The two companies even share some major investors. As Margins contributor Adam Connor laid out in June 2020, TikTok had begun an advertising blitzkrieg in 2018:

We do know that armed with cash, ByteDance undertook an advertising campaign that was reported by the Wall Street Journal to be more than $1 billion dollars in 2018. That breaks down to nearly $3 million dollars in advertising daily. This included nearly $300 million on Google advertisements for TikTok in 2018. There were so many ads that you could find threads on Reddit and other places on how to get rid of the TikTok ads users were seeing (and a lot of offline ads too).

As TikTok was buying its way into American headspace, all it’d take was a tiny tweak in favoring the Shein hashtag to propel the company to global domination. TikTok is also built on a non-follower-based algorithm, meaning anyone who posted the Shein hashtag could be rewarded with virality, incentivizing them to post about Shein even more. TikTok users were being presented with this new, insanely cheap shopping experience. Everyone wins. It’d be such a simple, clean partnership.

The Tech Cold War

I don’t write this in an accusatory manner. This is Partnerships 101 and I’d almost be disappointed if this somehow was all magically organic. However, I do think this is important because of the conversation around the US and China “tech cold war.” In May 2019, I wrote about TikTok:

I still can't believe its not a bigger story that a Chinese-owned app is quietly taking over the American market. I'm very curious to see what level of American headspace will have to be occupied by TikTok before it ends up on CFIUS's radar. Maybe their members just haven't downloaded it yet.

TikTok is certainly top of mind now for U.S. policymakers, but we’re oddly only focused on whether the user data resides on Chinese servers (Shoshana Wodinsky has done great writing on the absurdity of focusing on where the data lives, though I disagree that it does matter who owns TikTok). I’m more interested in the idea that a black-box algorithm that has come to create and define American culture is built and controlled by a Chinese company (go read this Ryan Broderick piece on how TikTok is where culture begins now). I’m even more interested if that algorithm is silently able to bring along another national champion for the ride.

The policy conversation tends to focus on data, microchips, AI, biotech, quantum computing and other sensitive industries. I think we need a renewed focus on how a few very opaque Chinese companies have (we don’t know anything about the Shein CEO!), in the span of a few years, come to control a much greater percentage of our culture. Shein needs to be included in this conversation - it’s quietly and completely changing consumer expectations around commerce. Dumping out a box of clothing because it’s so damn cheap still blows my mind!

We need to explore how these companies built off each other—TikTok propelled Shein—and what that means for the Tech Cold War. I write this cautiously because I know one can easily attribute a xenophobic undertone, but I genuinely believe the ‘tech cold war’ will be one of the more geopolitical stories of this decade. This stuff is important and it’s not going to just be about who controls the highly sophisticated computing industries. Commerce is another front in the tech cold war that hasn’t really been in the conversation yet, and it should be.

#TemuInfluencer

One last fun part of this story: Pinduoduo quietly launched their own U.S. presence with the site Temu.

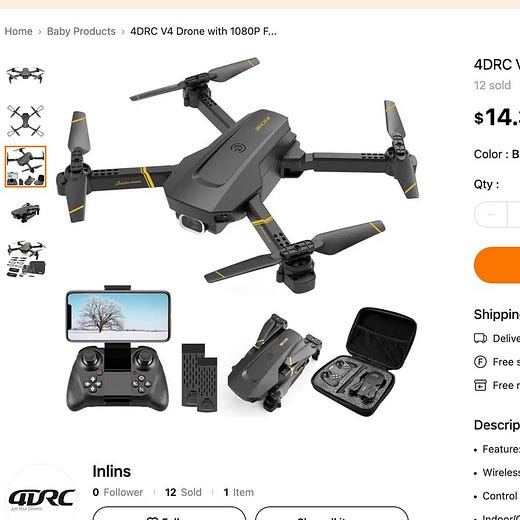

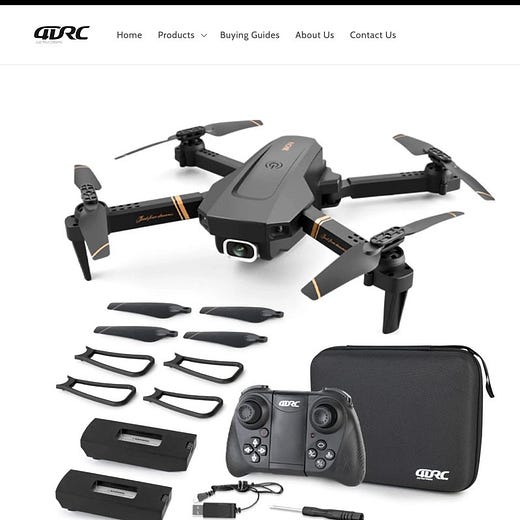

In exploring this piece, I bought a bunch of stuff on Temu just to see how it worked. Maybe I’ve just become one of the first American Temu influencers:

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

Note 1: There are endless studies where you see “Gen Z wants to buy sustainable products.” My favorite research remains this McKinsey / Business of Fashion 2019 report that defines the “woke consumer” in this dry, analytical, consultant-y way:

Signs of this evolving agenda can be found beyond consumer sentiment too. Fashion companies are showing signs of getting “woke” (a phrase defined as “alert to injustice in society,” popularised on social media). For example, based on a “data scrape” of over 2,000 fashion retailers, the appearance of the word “feminist” on homepages and newsletters increased by a factor of more than five from 2016 to 2018.

Note 2: This press release where Shein announced it’s rebrand from the name SheInside is one of the oddest things I’ve ever read. It’s still wild to think this is how one of the biggest retailers in the world was communicating a major rebrand just a few years ago:

Before changing the brand name, Sheinside held a worldwide slogan competition and after half a month voting and selecting, the winning slogan emerged. "She In, Shine Out" is exactly the embodiment of SheIn. This wide-range of activity has sparked heated participation and it is also regarded as warm up of brand name changing. Compared to the prior brand name, SheIn is easily recognized and remembered. It also fits in with the company's corporate culture. "She wants in your heart rather than just to be by your side."

Note 3: I think we can credit Packy with the term real-time fashion? I looked around and couldn’t find it anywhere earlier.

Great write up as always.

The opacity is why I refuse to participate in TikTok et al. Not knowing where your data is going is Step #1 in how it ends up in bad hands.