Late Stage Prisoners Dilemma

Tigers and hedge fund hotel parties

Ranjan here. This week I’ll be writing about the Tiger Global venture model and late-stage private markets.

It’s becoming more clear there will be many more tides washed out and emperors de-robed in the coming months. I’m convinced some of the most intriguing stories yet to be written will come out of the world of Tiger-style late-stage private startup funding (not that there’s any shortage of interesting in the markets right now). The style is often called hedge-fund crossover investing as it’s traditionally public market investors crossing over into private markets. For shorthand I’ll refer to it as HFC investing.

The Tiger

I’m sure most Margins readers are somewhat familiar with the Tiger Global HFC strategy. If you haven’t already, I’d recommend The Generalist’s Tiger Global: How to Win or Everett Randle’s Playing Different Games to get a better picture. Both pieces dive into how Tiger Global developed a Softbank-ian strategy of throwing more money, at a faster speed, while being insensitive to price. Randle used some great descriptors like “Better/Faster/Cheaper Capital” and “Maximum Deployment Velocity”.

Tiger could move faster by outsourcing deal diligence to Bain consultants. They would pay well above asking prices to quickly win deals. They wouldn’t ask for board seats or get overly involved in a startup’s strategic direction.

The scale of this became crazy as Tiger became the most active private-market investor around in 2021 (and remained the ‘spendiest’ in Q1 2022):

In 2021, the investment firm backed 335 deals — up 324% from 2020’s 79, and more than any other investor globally. That equates to 1.3 deals per business day.

Everyone talks about the speed and size, but just as interesting to me is the group dynamic often pursued with the HFC style. In a lot of these rounds, you’d see the same usual suspects teaming up to pour money into a late-stage startup. I’ll call this the a hotel party round, to clumsily combine the public market term hedge fund hotel (where hedge funds crowd into a trade together) with the classic venture term of party round (where everyone’s clamoring to get in). Maybe this’ll stick, maybe it won’t, but I have to try (Note 1).

This shining example of fast, cheap, and plentiful money finding its way into non-traditional places (sound familiar?) is something I’ve certainly been watching closely (Note 2).

Party Time

It wasn’t just Tiger. There was slew of hedge funds, sovereign wealth funds, and formerly-public market only institutional money diving into the strategy:

And the strategy worked. As someone who previously worked in emerging markets trading, the ability of a few well-resourced players to set and drive a price is something I’ve very much been on the very wrong end of (read about me getting smacked by the Dong).

For an example, let’s walk through the recent history of the cybersecurity company Laceworks.

It raised an $8mm A in 2015 from traditional VC. It raised (another?) A of $24m in 2018 from a bunch of normie venture. In Sept 2019 it raised $42mm, mostly as follow-ons. All seemed vanilla.

Fast forward to January 2021.

Out of nowhere there was a gigantic Series C of $525mm. Tiger, Dragoneer, D1, Coatue, and Altimeter were all involved. Yes, you could argue maybe this funding made sense. It was over a year since the last round, we were well into the pandemic, and cybersecurity was on fire, but the scale of the funding is certainly notable.

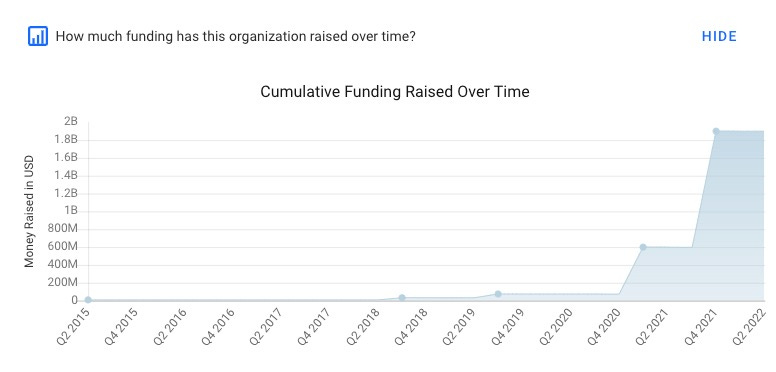

Just 10 months later, in November 2021, Laceworks raised $1.3 billion. It was, once again, the usual HFC suspects joined by some even more buttoned-up money like Franklin Templeton and Morgan Stanley. This really is a beautiful graph of Maximum Deployment Velocity:

I’m sure 2021 was a good year for the business. Cybersecurity would certainly produce some giants. Lacework reportedly tripled Q3 2021 revenue YoY. They hired the former a former Facebook engineering VP.

It’s the perfect embodiment of the HFC strategy. Take a company that was likely solid and in a hot sector. In Jan 2021, markets were already going crazy. You then team up with your friends and pour a bunch of money into it, and then just a few months later, you all pour even more money into it. Everyone happily pays an exorbitant price because it means everyone gets to mark up their books. Everyone could then go out and raise new funds by marketing those unrealized results. In a business where you get paid a percentage of assets under management, it’s a no-brainer. As of a few months ago, you might even be able to flip the company to the public markets at that high price.

Signaling

One additional detail to note is that Nov 2021 “record-setting” Laceworks round had a very public valuation of $8.3 billion.

Do you all remember the old days when companies and investors actively worked to avoid valuations leaking to the press? One element of the HFC strategy has been making very transparent valuation proclamations for late-stage rounds. Skims (D1 and Lone Pine) is worth $3.2 billion. Ramp (D1, Coatue, Lone Pine) is worth $3.9 billion. You see it over and over in any HFC press coverage.

This feels like one of the more under-appreciated parts of the HFC strategy. In the past, investors would have looked at the price they paid as proprietary info. The secrecy could help you negotiate the next investment. Now, it’s transformed into a signaling mechanism to the public markets and retail investors. In boom times, the leaked valuation effectively sets a baseline idea of a company’s worth. Laceworks is now worth $8.3 billion. When it’s time to IPO, that’s the starting point in the conversation. Over the past few years, with endless capital and investor appetite it worked beautifully.

Another notable element from the Laceworks example is that investors got to mark their initial January 2021 investments at that $8.3 billion level in November. Tiger and the HFC crew 4 or 5x’ed the January money with their own follow-on investment. They could then take those results to go out and raise. And they did. In March, Tiger announced a gigantic $12.7 billion growth fund, that was reportedly raised in “less than four months” (I’ll let you do the calendar math).

And the final amazing part of all this - these inflated private market valuations have helped prop up Team HFC through their public market carnage:

D1’s hedge fund was up 26% in 2021, powered by a 70% gain in its private holdings as its public portfolio fell 8%, while at Tiger Global, the hedge fund’s 7% decline last year compared with a 54% rise in its Private Investment Partners funds.

In Q4 2021, the public markets started shaking out but private market valuations were still marked based on these big HFC rounds where this small group of players effectively set the price.

Game Theory

Let’s now look at the game theory of all this. The most intriguing part of these HFC-backed companies is almost no one in the group has a vested interest in seeing the valuations come down. It’s this amazing tightrope where, as long as the startup can avoid an emergency funding round, the valuation can remain inflated. The HFCs and VCs want to avoid a markdown. The LPs (people who put money into the HFCs and VCs) aren’t clamoring for markdowns. Startups would rather not get marked down.

But the IPO market is dead meaning there is no clear exit anymore while public market comparable companies have been crushed. Just look at payments - it was a big story that Stripe was marked down by 9%. Meanwhile, Paypal is down 60%. Square is down 54%. Adyen is down 54%. It’s a perfect encapsulation of private market insulation. Everyone knows Stripe is worth less, but as long as we all don’t say Stripe is worth less, we can pretend it’s not worth less.

Everyone is praying the macro-economic outlook turns around, consumers feel great again, the IPO market opens up, and public market appetite comes back. I picture everyone sitting around a table, just looking at each other and sweating.

Prisoner’s Dilemma

In almost no scenario should those inflated private valuations hold. Even in the best-case scenario, a startup follows the suddenly-in-vogue pivot to generating cash, but that means they’ll have to slash growth. Those gigantic valuations were modeled on assumptions of strong growth and become dead in the water. But if startups don’t do this, they’ll need to go out and raise more, inevitably repricing to a down round. Given the state of the economy, public market comparables, waning consumer demand, and a million other negative factors, it’s clear companies should be revisiting those valuations.

The biggest question right now is what could trigger these revaluations?

Will it be the LPs who start the markdowns? I spoke with a friend in the industry who said there are certain provisions for institutional investors where audits and markdowns can and will quietly take place. Maybe that’s why you always hear the name Fidelity whenever some news of a markdown leaks to the press. Will Fidelity quietly be the HFC grim reaper?

Even as far back as 2015 this was a known potential:

So we’re back to that table where everyone’s sweating. Who will budge first? What incentives are there for any of the players involved to mark down the investment?

Hanging by a thread

The sweat and stress is compounded by the fact that most of these HFCs are in a precarious position. Their public market funds have been obliterated over the past few months. The Tiger numbers have been wild:

Given that there were 82 trading days in January-April, this works out to be a loss of roughly $183mn every day that markets were open this year. Or $28.1mn every hour that US markets were open. It’s almost impressive.

These elevated private valuations are Tiger’s lifeline right now. It is existential they’re not marked down.

It’s also worth thinking about how personal this all can be. At that table where everyone is sweating, a lot of these funds are known as Tiger Cubs [Note 4]. They made their way up in the world together. They often wear tuxedos. Even the ones who aren’t Tiger Cubs have dealt with each other for years.

When you’re all sitting at the table, do you want to be the first one to mark down a company and set off any number of unforeseen consequences for the people you made your way up in the world with and who all have shared financial interests?

Who gives first and why?

Human Drama

Every cycle has its own poster-child and this model of gigantic public capital moving into private markets is unprecedented for this current vintage. The dynamics are so unique because the markets are opaque, the players set the price, there’s no ability to short, and everyone involved has an interest to not mark assets down.

This story will be even more riveting as it will play out as a genuine human drama. This won’t be your buddy watching $LUNA collapse on a screen. For this kind of drama it will be phone calls and press leaks. It’ll be mutual fund risk managers in skyscrapers, furious text messages, and fleece vests. Maybe us mere mortals will never even see it happening. Or maybe there will be contagion. That’s the thing about illiquid, opaque markets filled with unprecedented wealth creation and the associated risk. Usually they make for good stories.

I recently watched Margin Call again. It nails the prisoner’s dilemma element of illiquid market dynamics. The movie has this ruthless, almost banal tone that perfectly captures how someone will start selling first and markets will be crushed (and everyone will still probably end up wealthy).

(had to record my TV with my phone so not the best quality)

Note 1: For fun, I pulled some Crunchbase data for D1, Lone Pine, Dragoneer, Tiger, and Coatue. There were 99 deals featuring 2 of them, 23 with 3 or more of those 5, and 2 deals with 4 of the investors. I’d be really curious if anyone has a more thorough analysis of these overlapping hotel party rounds (could throw in Altimeter and any other number of funds).

Note 2: ZIRP wasn’t the first time I was intrigued by money finding it’s way into unexpected places. As a former emerging markets trader, the idea of “Tourist Dollars” was a regular idea that I wrote about back in 2016.

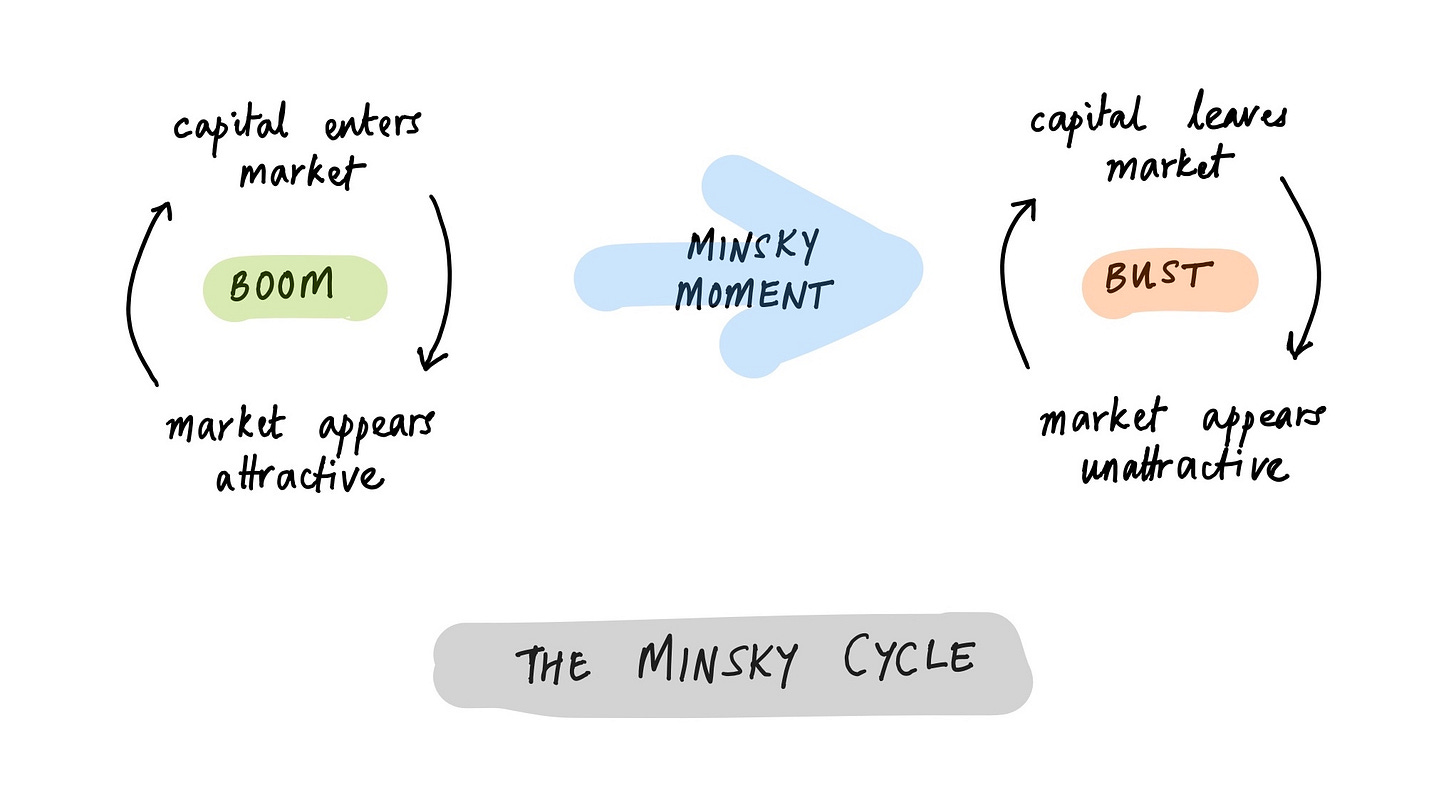

Note 3: A big question I didn’t address here is what additional fallout there might be. There was a great piece called the Minsky Moment in venture capital, about how all the circular dynamics that drove capital into private markets could reverse:

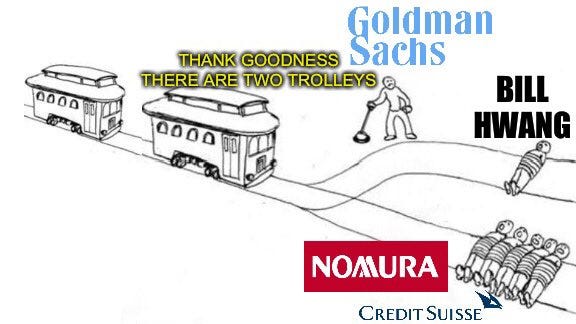

Note 4: A friendly reminder that Bill Hwang was a Tiger Cub. Also, a nice reminder that Archegos had its own amazing prisoner’s dilemma where Goldman got out first.

So what's a startup do to, when you want to sell product not shares? I have enough risk pursuing our chips breakthrough without taking on the risk of a Wall Street meltdown that has really nothing to do with our business. I really don't want to get painted with somebody's scam. Seems there's a Gresham's Law operating here: the Tigers, win or lose, drive out the careful DD/low price/patient money kind of money.

Nicely Explains how venture could be a house of cards and the mechanics behind it. Kind of like the 2008 housing bubble where no one had an incentive to set the correct price for things or be the canary in the coal mine.

But, I wonder what the mechanics are behind the current housing bubble. Any ideas?