Science, how does it work?

Or does it even work?

Hi. Can here. Today, I’m going to talk to you about science.

Suppose you are taking a medical test that is 99% accurate. The test is for a terminal disease; you have it, you die. Obviously, if you test positive, it is terrible news. But what about if the test comes out negative? Should you be concerned or relieved? Clearly, it's not as bad as testing positive, but if you knew beforehand the test was only 99% accurate, you know that there's a chance that the test is wrong? Right?

Actually, wrong. Well, maybe. The point is thinking about this test in terms of accuracy is the wrong way to think about it. The right way is to forget about accuracy but focus on the false positive and false negatives. My coworker Ranjan talked about this once, and I sort of riffed on the same idea before in terms of hiring, but the idea is the same.

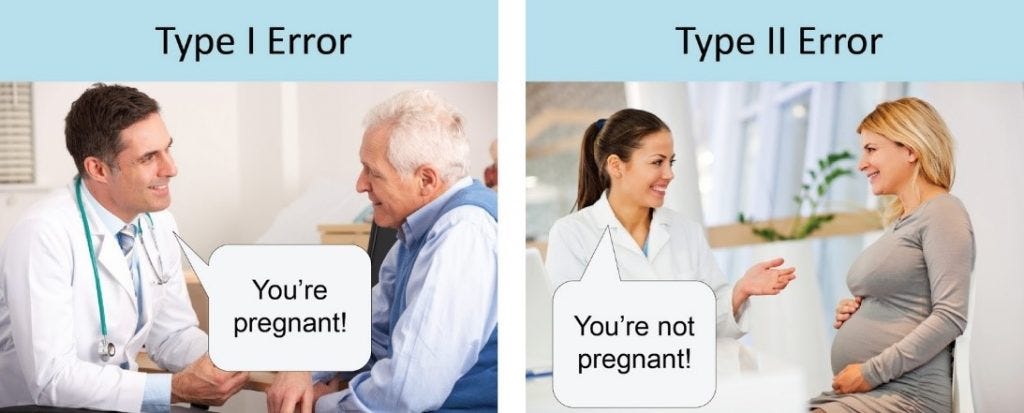

There are two possible states you can be in: sick or healthy. And the test might be positive (i.e., you have the disease) or negative. You would want the test to come out positive in 100% of the cases of you being sick, and negative every time you are not. But this is easier said than done. Most of the time, it is impossible.

I don't want to bore you with the details, and I am nowhere near qualified to comment on most things biology or medicine, but you can imagine why this stuff is hard. Getting a test to show negative is easy, but making sure that you cross a specific bar to test positive via measuring the quantity of something is always going to be a judgement call. You’ll definitely make mistakes one way or the other.

Let's say you are measuring something like the viral load. First of all, you have to somehow turn something analog and continuous into digital and discrete. This itself is a huge problem. Whatever threshold you set, it'll be wrong for someone, somewhere. If you test too early, you won't have enough antibodies. If you check too late, the disease might be too far advanced. Second, we already know that undetectable viral loads do not mean that you are cured; it just means that we can’t detect it. It is good news for the patient, but it’s humbling for science.

It is easy to get bogged down in the details of the science and the statistics of a single test, but they matter. Going back to our example, there are downsides to telling a healthy person that they are sick, but they are primarily individual risks. The potential societal downside of telling an infected person, who can get others sick, that they are healthy is much more significant.

We talked about the tendency of the technorati to co-opt the language of science without actually understanding the spirit of it here before. I also wrote about it years ago, in the context of pretending that accents are indicators of failure in business. My co-host Ranjan likes to say our Margins piece was our most prescient writing for the information crisis we are having the wake of Covid-19 in 2020. I don't know if I'd go that far, but it rings true.

In the Margins piece, I simply wanted to point out the dangers of motivated reasoning. A researcher who was hell-bent in arriving at a particular outcome, I argued, would generally arrive at that outcome. A single paper, I tried to say, should never be taken as gospel. The currency of pursuit of knowledge is not headlines, but a slow and steady reduction in doubt. It is also an asymptotic relationship with the truth. You will edge ever so closer with time, but you’ll never get there. That is a not a bug, but a feature.

One way to look at the scientific method is to consider it a set of rules and conventions aimed at eliminating all our human flaws in the pursuit of knowledge without judgment. The process does not care whether you wanted to swing the results one way because you wanted to get funding, or you just did it by accident. It doesn't matter. There is no judgment here, but merely the admission that individuals are fundamentally flawed at every step of the way.

We are unable to design experiments, unable to run them, and are unable to interpret our results. We can't get anything done without introducing our biases, knowingly or not. We can't measure things right, nor can we write them up without errors. Even if we could see things clearly, we would never know what we are really seeing.

Go back to that medical test I brought up in the beginning. It's already hard enough to come up with a single medical test that we can interpret, but let's say we have a handle for the time being. Now imagine you want to use that test to see if a drug does work to treat this disease. You start with assuming it does not, and then figure out the threshold by which you can claim it does.

And once that's done, you have to recruit subjects as randomly as possible. You have to not treat some, and fake it on others. Your team has to know what they are doing, to do the right thing, but not know too much. They need to know how to do their job, but now what they are doing to not tip their hands to those getting the placebo. Even a simple swab is not so simple.

The subjects need to be informed, but not too informed to do anything to affect the results. You need to measure things at every step, but not peek at the results until the very end. When it comes to collating the results, you need to be faithful to your original assumptions and design, but also know how and when to clean your data. You need to eliminate the outliers, but not the ones that matter. I could go on and on

There are simply too many steps in all this for a single researcher to not make a mistake. Multiple people in a team can either catch others' mistakes, but each individual can also contribute their own, and compound others'. And remember: each of these is also a button that a less ethical researcher can use to push the results in one direction or the other.

I know this can appear as me nitpicking, but all of these happen with shocking regularity. There are entire fields whose reputations got wiped out by decades of sloppy research done by generations of well-intentioned, highly skilled researchers. What is a seminal paper one year gets redacted the next. The more striking and applicable a finding is, and more it has diffused itself from the hallways of university campuses to common knowledge, the more dramatic it is when it gets debunked by other researchers years later. WEIRD is a thing, and people have found basic Microsoft Excel errors in Piketty's research.

And yet, where does this leave us all? Should we be skeptical at all times, and never trust any expert? If things are so hard to know, so impossible to ascertain, how on earth do us busy individuals make sense of this all? As unforgiving as they may appear, the scientific method and the guidelines established by the community can be useful here.

First of all, we should be very skeptical of things that sound too good to be true, as they most often are. We should demand extraordinary evidence from extraordinary claims. We should acknowledge our own motivations at every step, and increase our mental bar for acceptance when a result appears to be in line with what we would want. And, maybe most important of all, we should demand evidence never from a single source, but from multiple, independent but dependable sources.

We are all facing an unprecedented unknown. Tens of thousands are already dead, and a bigger number will have perished before we are back to an acceptable routine in what will be our new normal. More than going back to where we were, I think, we all want answers to feel a bit more in control.

I am not qualified to give anyone a false sense of security for the days ahead. Most of the people you interact with daily are not either. I am, however, qualified to tell you that the answers you are looking for will not come from random Medium posts or tweets. There will neither be a simple malaria drug that fixes everything, nor will it be a shocking finding like runners or cell towers spreading a viral contagion.

The solution we are going to arrive is going to look like nothing like we had before because we had nothing like this before. However, the worst thing we can do now is to believe in false miracles and magic cures. We already know how to make this work.