Robinhood and How to Lose Money

Don't be the gravy

Ranjan here. Today I’m writing on Robinhood, what investing means to me, and whether you should be trading options.

For someone who clearly has strong opinions they enjoy communicating with others, investing occupies a weird place for me.

I have stared at markets, tick-by-tick, for tens of thousands of hours. I spent nearly eight years as a trader, and as I was trading mostly Asian markets in a NY office, staring at those screens would often extend to sometimes 24-hour cycles. I can tell you every price fluctuation in AAPL since 2007 or the VIX since 2014. I love this stuff.

Yet I’m incredibly cautious in how and when I talk about it. Investing is a very personal thing for me. It's taken me on incredible journeys and made my life a helluva lot more comfortable than it otherwise would've been. But, for the most part, my investing is this quiet space where it's just me and the markets. Don't get me wrong. I’ll talk your ear off about economics and the markets. I just won’t talk about specific trades, and especially, position sizes.

It's mainly because, over the years, I've learned that a general rule is anytime anyone tells you about an investment, you shouldn't listen. They're most likely telling you a quarter of the full story, or they're trying to sell you some investment newsletter, or maybe some newfangled financial product, or just getting in a good old-fashion dick-swinging competition, but in investing, more than probably any other area of life, assume everyone is at least partially lying.

Which, naturally, brings me to Robinhood.

GIVE ME SOME FRICTION

I've been following the company very closely for years now. I was always a bit confused by the allure of zero-commission trading. At worst, those $5 Fidelity trade fees were the price of a sense infrastructural security and business model transparency; I’m paying for a stable and transparent trading environment. At best, it was a behavioral roadblock from trading too much.

I opened up a Robinhood account very early on, but for me, the mobile-only functionality was a dealbreaker. I didn't want to be trading "on-the-go". If I wasn't sitting at a desk, in front of a large screen, fully at attention, it was best not to trade. Sitting at a desktop is a different mindset, and that’s where I wanted to be if I was transacting. Fidelity's mobile apps were "fine" if there was some kind of trading emergency where I needed to transact suddenly.

I’d argue that trading fees and not-great mobile experiences both, oddly enough, made me a better investor.

I was much more interested in how the hell Robinhood made money. While the universal rule of "everyone talking about their investments is partially lying" might not be a widespread axiom, the rule of "if you're not paying, you are the product" is a bit more well-known.

MAKING SPREAD

In writing this post, I was trying to find when I first learned about how Robinhood routes their order flow to shops like Citadel Securities. According to my Instapaper archives, it was April 2017. From some googling around, this Hacker News thread from December 2013 is the first instance I can find of "Robinhood Citadel".

For those unfamiliar with what ‘routing order flow’ means, it might help to explain how my job in bank trading as a market-maker worked:

Most people associate being a "trader" as taking bets all day. That's not most traders at banks do. As a market-maker, your job was to....make a market. I traded foreign currency products, and FX is probably the easiest way to understand this for most people.

When you go to a foreign exchange teller at an airport, for each currency, you'll see two prices. It can be confusing to understand the exact rate you'll get, but that's kind of the point. The only safe assumption is you will have your face utterly ripped off. Again, that's the point.

This is an extreme example of market-making. Travelex or whoever is running the stand doesn't care whether you need to buy or sell EUR or USD or HKD or CHF. They make money every time you transact. It works well because, for the most part, the customer needs the transaction done immediately and they don't understand the true cost. It’s why Travelex doesn’t say something like “to exchange $100 into EUR, I will charge you $9.”

Now extend this onto a large bank trading floor with hundreds of people staring at screens and shouting into phones. A typical transaction for me could've looked like:

Note, my description of how this all works is circa 2009, and things are a lot more automated, but the concept of market-making is the same:

A salesperson is talking to their institutional client that's a pension fund manager. The client is exploring Thai Bonds and, if they trade, they’ll have an associated currency transaction needed.

The salesperson wants the client to trade as their compensation is usually based on a complex commission structure (a percentage of an assumed spread).

If the client is ready to trade, the salesperson would call over and ask me, the trader, for "a price". I'd provide a bid and an offer, and the salesperson would shout over whether the client "dealt" and "which way" they dealt - meaning, whether they bought or sold.

The great and beautiful tension came from how wide the bid-ask spread the trader makes was. The trader’s incentive was to try to get the deal done, but also make as much money as they could off of it.

The client was likely, at that moment, asking multiple banks. Salespeople at different banks were yelling at their traders to "tighten up that spread, it's so wide you could drive a truck through it" because if the client didn't deal with them, they wouldn't get their commission.

At a large bank, most of your clients were institutional, meaning they were pension and hedge funds. They were sophisticated investors that were ready to dance. The "client" was an execution trader at a large fund whose compensation was directly tied to getting the best possible price. They were talking to the salesperson whose compensation was tied directly to getting the client to trade. As the trader, my compensation was tied directly to how well I could manage the risk involved in getting the trade done.

I always did love just how unabashedly capitalistic these interactions were. Every party involved had an aggressive and clear profit-making motive. There was cajoling and yelling and nudging all happening in real-time in this great, collective exercise to find the most efficient capital transaction and there was just a lot of money to be made.

But those were the institutional clients.

There was also "the gravy".

These were the less sophisticated clients. These were fewer and further between, but when they came, it was a breath of fresh air for everyone involved. It could be a risk manager in a corporate treasury group who played golf with the bank salesperson. They didn't follow these markets and didn't really care. Their compensation was not directly tied to infinitesimal basis point spread calculations. They would call in the deal, the salesperson would call over for a price, and I'd happily make the price, knowing the person on the other side didn't really care. It was like the person who just landed for vacation looking to get taxi money at the airport. A deal needed to be done and they didn’t really care about the price.

There are clearly many more levels to the above explanation, but the most important thing to remember is, the entire trading floor was set up to make clients trade more. Every bonus structure and every job title and every five-year strategic plan was about getting people transacting. And the more gravy, the better.

Robinhood traders, y'all are the gravy.

And I’m not just saying that. The recent NY Times feature on Robinhood quantifies it:

This practice is not new, and retail brokers such as E-Trade and Schwab also do it. But Robinhood makes significantly more than they do for each stock share and options contract sent to the professional trading firms, the filings show.

For each share of stock traded, Robinhood made four to 15 times more than Schwab in the most recent quarter, according to the filings. In total, Robinhood got $18,955 from the trading firms for every dollar in the average customer account, while Schwab made $195, the Alphacution analysis shows. Industry experts said this was most likely because the trading firms believed they could score the easiest profits from Robinhood customers.

The professional trading firms like Citadel Securities are literally begging for Robinhood orders.

SILICON VALLEY AND FINANCE

I hadn't processed just how perfectly Robinhood has silicon valley-ified financial markets until I started writing this post. Robinhood is Facebook is Google is everything else. Just look at the story:

Stanford (or insert other top-level school here) grads head out to disrupt a market that genuinely needs to be disrupted.

The great disruption is things will become free. Everything is couched in the language of democratization. The Robinhood founders even push the origin story that the idea was born amidst the Occupy Wall Street protests 👀.

As with most "free" products, the real business model is based on engagement. The more time you transact and interact on the platform, the more money the platform makes.

The product is built to trigger every possible dopamine receptor in a user's brain. In the early years, terms like gamified UX are considered a positive.

The company grows to an incredible size and the founders and investors and lots of people working there get incredibly rich.

We slowly start to see a litany of unintended consequences, but for the most part, it's too late and the cultural impact has already taken place.

I enjoy bantering with my co-host Can about the similarities and differences between Silicon Valley and Wall Street. Robinhood is just another market-making operation, but instead of a salesperson in Gucci-bit loafers getting you a tee time at Winged Foot to encourage you to deal, it's UX designers building in algorithmic nudges. But the goal is the same. Trade more.

And this gets back to what I view as one of the biggest dangers about the way Robinhood is built.

I don't imagine during their early conversations about building the product, the Robinhood founders said things like "let's build an addictive platform to encourage novices to overtrade at bad prices so we can profitably route their order flow to large financial firms like Citadel Securities whose founder bought the most expensive home in the US”.

I don't think they approached this with the mindset of a boiler room calling up retirees and aggressively pushing them to buy shady stocks.

I'm also guessing they were not actually Occupy Wall Streeters looking to genuinely democratize access to financial services.

My bet would be they just wanted to build a startup rocketship and this was the best market opportunity. From their Product Hunt launch, everything was about viral growth from day one (yes, I autotweeted to 'move up the waiting list').

The hypergrowth is not the means, but the end in itself. There was no consideration about the impact of the user behaviors they encouraged because everything was just a number on a dashboard.

Maybe they really did want to introduce investing to a whole new generation and make it easier to access. But they also likely never thought through the consequences of how they were going about it. Just like Mark Zuckerberg wasn't anticipating a genocide in Myanmar, I'm sure the founders in no way imagined the suicide of a twenty-year old.

LOSING MONEY

I started this piece commenting on how I'm fairly private in my investing. However, I'll end this piece sharing more than I typically would. I put most of my savings into AAPL before I left trading for business school in 2009. That clearly worked beyond my wildest expectations, but any investment advisor would've slapped me across the face for how reckless it was. I never traded an option before 2015. I happened to buy a bunch of S&P puts in August 2015, and completely by luck made a lot of money on the Chinese devaluation. In fact, I had no idea how I made that much money that fast because I didn’t really understand options.

As most of these stories really go, I began over-trading and lost all those gains and more. And then, as I hope most of these stories can go, I pulled my shit together, became more disciplined, and still happily trade options as part of my overall investing.

It feels like the typical "hero's journey" story arc, but I hesitate in writing that because another important lesson in investing is 'don’t be a hero'.

I say this all because I’m happy I went through the experience of losing a chunk of money at a time in my life where I could. During the heady AAPL days and the put-options-gone-wrong days nothing about my life or spending habits significantly changed. I mean, I guess I was professionally trained to emotionally and mentally handle this kind of stuff, but it really has been a really valuable and important journey.

And these experiences make me a bit libertarian in the sense that I think it's as important for people to learn to lose money as it is to make it. In that New York Times piece they tell a story of a guy who turned $75k into $1 million and then lost $994k of that. I don’t feel particularly bad for him. It’s terrifying he was able to take out credit card and home equity debt to fund that first $75k, but otherwise, the risk involved in making a quick million means you can lose it just as fast.

Going through investing ups and downs in my (relatively) younger years will not only make me a better investor for the rest of my life, I think it made me more grounded in general.

OPTIONALITY

But it was all on my own accord. I felt in full control. In fact, I remember Fidelity making it a pain in the ass to start trading options and being on the phone with customer service for an hour about some missing form. There were guardrails and friction in place. No one encouraged any of it and I got to make my own mistakes.

That's the part that really worries me about Robinhood. Every non-finance friend of mine is sharing screenshots of options trades. This is a company that built a reputation on their UX prowess and I do believe they can influence behavior. And trading options can be really exhilarating. It gives you much more of the casino rush than buying and holding stocks, or even buying and selling stocks.

And they’ve built a product that has gotten their customers to trade a lot of options. Again, from the NYT:

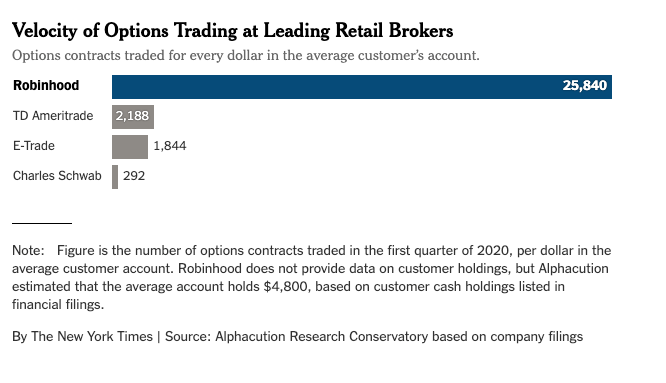

In the first three months of 2020, Robinhood users traded nine times as many shares as E-Trade customers, and 40 times as many shares as Charles Schwab customers, per dollar in the average customer account in the most recent quarter. They also bought and sold 88 times as many risky options contracts as Schwab customers, relative to the average account size, according to the analysis.

And let’s remember that options are far more illiquid and opaque than standard equities. Opacity and illiquidity are two things that make market-makers salivate, with visions of mile-wide bid-ask spreads dancing in their heads.

And now combine that with an unsophisticated customer who is barely familiar with the pricing mechanics of the platform.

You could not craft a more desirable scenario for Robinhood and everyone else in the trading supply chain. And I can’t imagine it’s a coincidence that the most potentially profitable product is the one being encouraged.

Learn to invest.

Lose and make money.

Enjoy the rush of trading if you want.

Even trade options if you want.

Just don’t be the gravy.

Note #1: I’ve written a few times about what I consider Silicon Valley doublespeak; couching rabidly aggressive capitalistic practices in hippie-ish language. I have to give Robinhood a ton of credit. Naming yourself after the character who stole from the rich to give to the poor, while making a ton of money off of your customers for, again, the billionaire who literally bought the most expensive house in America, could make even Adam Neumann blush.

Note #2: There’s some good online debate about how the NYT got to the figures on options velocity and payment order flow revenue per user. The main, and reasonable, complaint is that things are overly magnified negatively for Robinhood because of how much smaller their average account sizes are.

This was kind of a cool format for someone saying it’s misleading:

And here is the NYT journalist providing how they arrived at the calculation:

I think it’s fair to say that the number $18,955 that was eye-popping could be a bit exaggerated, but we shouldn’t overcomplicate things. Unsophisticated investors trading opaque markets will always be, almost by definition, the most profitable customers to make markets for. Y’all are definitely still the gravy.

Note #3: I went to Emory for undergrad, and one of my first internships was at a day trading firm in Atlanta during the go-go internet bubble days. During that summer, a day trader who had lost a bunch of money killed his wife and two kids and then went into the Buckhead trading firm where he had been fired from and killed another nine people. It was fucking terrifying. The detail that Robinhood had bulletproof glass installed at their offices definitely made my stomach turn a little bit.

Hello, I'm contacting you on behalf of Citadel Securities, I work for their PR agency. The article inaccurately states that Robinhood routes orders to Citadel. Citadel is the hedge fund and Citadel Securities the market maker; they are two entirely separate entities. The references to Citadel should thus be Citadel Securities. Would it be possible to make the necessary corrections please? Feel free to contact me if you have any questions: eleonore.basle@greentarget.co.uk

Ranjan, fascinating piece. Love how you get straight to the bone. You mentioned that Robinhood's secret sauce is their dopamine secreting UX/UI. Would love if you could dissect that in detail in one of your future posts.