Ranjan here. I've tried to avoid writing two Margins’ pieces on the same subject in a row, but the topic of essential worker safety is so of this exact minute, I needed to write on it again (the last one was how the CARES Act would affect labor supply).

There have been a lot of pieces on whether it's ethical to shop online right now. I’m still searching for the right “answer” and haven’t found it. My current stance has been to go grocery shopping while being as careful as possible: mask, gloves, and distancing.

I understand that:

I'm putting myself and my family at risk by leaving the house.

However, I'm not transferring that risk to an Instacart shopper or Amazon/Freshdirect delivery person.

I'm putting the grocery store cashier at increased risk just by being there.

I'm lowering the pressure on the warehouse workers who would've managed an online order.

I still am ordering some stuff online and have been making a point of ordering directly from brands instead of Amazon, where possible. I've done curbside pickup from Best Buy and Home Depot.

I won't pretend there is an easy answer to any of this. But the one clear, simple and right thing is we should all be collectively ruthless in demanding protection for any workers putting themselves at risk to enable the rest of us to stay at home.

We’re currently not.

INVISIBLE INFRASTRUCTURE

In the pre-pandemic times, the conversation about technology removing human interactions from consumption was an intellectually fun one to debate. I sometimes send out my laundry, and always felt weird just leaving it outside the door after the Folded guy buzzed into the building. I’d wait until he came to the door, hand over the laundry bag and stick in a simple "thanks man". Maybe it was more for me than him, but it made the whole thing feel more human.

Amazon has clearly been the leader in the dehumanization of commerce, and I use that term dehumanization in a technical, rather than value-oriented sense. It's just what they've done. You buy something and often have no idea where it came from, who's selling it, who packs it up and who puts it on your doorstep. To their credit, it all just worked. The entire supply chain was made invisible and it’s amazing.

But it allowed us all to slowly remove any comprehension of the real people making the thing run. They did their thing and we clicked buy. It's made it a whole lot easier right now to be angry about not being able to schedule an Instacart delivery. That people feel reasonable in publicly complaining about this captures the problem perfectly.

Things take longer because these services are not built to handle this demand even in normal times. More deliveries, by definition, mean more “shoppers” crowded into the same grocery store. Ensuring worker safety will invariably lower overall efficiency and slow the whole thing down. It means fewer people in the grocery store. Long wait times and fewer delivery windows should be celebrated. It means there's at least a chance workers are being kept safe.

SIMPLE MATH

We all need to acknowledge the way that the retailers who have cashed in the most from the pandemic have approached worker safety has been a clusterfuck. Literally. That is the word used by a Costco worker in this heartwrenching piece from Buzzfeed:

Amanda Rosado, a deli worker at Costco’s Port Chester, New York, location told BuzzFeed News that by this month four of her coworkers had tested positive for COVID-19, a situation she described as “a holy fucking clusterfuck.”

The first Amazon warehouse worker (who was only 35) just died.

Walmart workers have died.

Dozens of grocery store workers have died.

As long as we are consuming, people are dying. The very least the work-from-home crowd could do is demand the first concern of every employer is the safety of their workers. We’re nowhere near that. Instacart recently got a ton of positive coverage around making their own hand sanitizer for shoppers. Yet, it’s still nearly impossible for Shoppers to get their hands on it. If this really mattered, the company should shut everything down until they figure out how to properly distribute PPE to their at-risk frontline. But it doesn't. It never did.

AMAZON

Amazon apparently already hired the 100,000 workers they announced in March, and are hiring another 75,000 more. The question we need to ask is: How will all this fulfillment take place?

The only way to make your workers safe is to have fewer people working in a fixed space. Staggered scheduling and social distancing are at the top of the checklist. And Amazon is a company notorious for pushing its workers to the limit (remember the pee-in-a-bottle stories?). Then, of course, facial protection, gloves, temperature checks, and general sanitization, which Amazon has not reliably provided for its workers.

So how is this going to work?

You cannot maintain the same per-worker-productivity. The pre-pandemic processes no longer function when there are (hopefully) fewer people who are (hopefully) safely further apart. Now you have a huge influx of orders needing to be managed in a relatively fixed amount of physical infrastructure. To ensure the safety of workers would require having fewer people working less intensely.

So what does this look like? Where do these additional 175,000 workers go?

Maybe it's new warehouses built from scratch? Maybe its some secret robotic exoskeleton (for how amazing the Echo products are, I wouldn't put it past them) that workers will wear? I pose the questions a bit tongue-in-cheek but am genuinely confused about the issue.

The one thing I've read that could possibly explain it is that Amazon has capacity built for the holiday rush (from Casey Newton, who’s been one of the few writers ahead of this story):

Even after 25 years, Amazon still tends to white-knuckle it through every holiday season, barely keeping up with demand despite months of preparation. The Journal story illustrates how every day of March was essentially Black Friday for the company. According to the analytics firm CommerceIQ, sales of home and kitchen items on Amazon are up 1,181 percent year over year.

But again, that is capacity built for a pre-pandemic warehouse. What do things look like now?

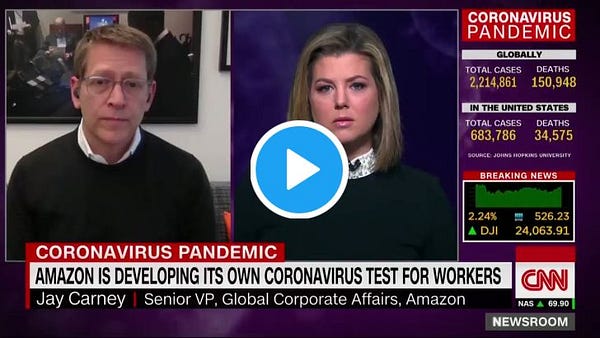

I wish I could ask this in good faith, but it's tough. Worker safety is a PR issue to be managed by singling out people they see as "not smart or articulate". They're firing workers for speaking out about safety. Jay Carey shows off his masterful Press Secretary-style obfuscation chops in avoiding answering a basic question:

The masters of data supposedly don't have data on the single most important thing they should know.

WHAT IS ETHICAL?

It’s always weird to see the Instacart shoppers in the grocery store. They usually have a bandana covering their face as they scan each item with their phone. And at the Manhattan Eataly I’ve been to a few times, they stand out because they’re mostly black and brown. Early on in the life of the Margins, I wrote about the technology-driven segmentation of society; that we were losing our shared physical spaces. Pandemic life takes this to a level I never could have imagined. The word inequality doesn’t even begin to capture what it feels like.

So what the hell can we do as individuals? Suit up and go to the store, or shop online?

This shouldn’t be binary. There are IRL places that treat their employees poorly, and ones where they are the primary concern. There are good online operations and bad ones.

Where do different companies fall in the spectrum? It's not always an easy question to answer, especially for a consumer. A number of unfortunate journalists have been on the receiving end of some lengthy rants from on the topic since late March, but the press needs to be merciless on this story. This is an issue that affects every single consuming American while melding together inequality, monopoly, class, and the COVID-19 pandemic in a way that nothing else does. This will define what our post-pandemic economy looks like. Informing consumers about who makes up the invisible infrastructure allowing them to subsist, and how those people are treated, is vital.

New York, New York

It's been fascinating watching my local grocery store evolve over the past month. They now have a security guard outside who allows a few people at a time into the store. All the cashiers are wearing masks and gloves as of a few weeks ago.

The other day I was in line and the most New York thing happened. A woman who looked to be in her 60s was in a shouting match with the security guard. She had a mask but no gloves and he wasn't going to let her in. Their policy had changed since the previous week and she was pissed. She screamed that she just needs to "get her fucking groceries" and he yelled back "I’m going to protect my people." She yelled back "I know you got to, but you're killing me here".

He, in that uniquely New York volume that confusingly lives in between an angry scream and a firm retort, where you're not really sure if the person is angry or just a New Yorker, yelled: "everyone just wait here for a moment."

He went inside and came out with a pair of gloves (cue Alicia Keys).

A happy note - last year while writing one of our first Margins’ newsletters, my wife went into labor:

Signing off til next week

....I planned on extending this post a bit more in the geopolitical context of Europe vs. China vs. the U.S., but….my wife just went into labor with our 2nd kid so I'll leave you to ponder the Forgotten Internet, and ask you to check in on your IFTTT and Zapier accounts, and cut off all apps connected to Facebook and Twitter. Wish us luck!

We just celebrated his first birthday and having friends and family virtually connect in ways we never did in the Before Times (a Zoom birthday party!) reminds me of the beauty of technology. As I’ve said before, I’m not technology cynical, just skeptical.

This is a great post thanks Ranjan.

It is thought provoking and something that many companies pivoting over here in London are struggling to answer.

As a person who had relied on deliveries and ordering from amazon & similar service we have some responsibility on asking difficult questions to ensure safety of the people putting their health on the line for a living wage