Focus is for winners

Bureaucracy dominates over strategy

Hi. Can here. Before you switch tabs, listen a bit.

A couple years ago, in a fit of contrarianism, I decided to unlearn to code and do an MBA. Upon graduating with a business degree, my father, ever the businessman, had a question: What did I learn at business school? Holding a business degree himself, but more importantly, having run a relatively successful business for more than a quarter of a century, he wanted to see where state of the art was. I told him that it’s hard to distill all the learnings of a year into a short, digestible answer but did come up with a short blurb: Inventory is bad, focus is good.

Focus, Focus, Focus. Or rather, Focus

We discussed the importance of focus here before. The main thrust of my argument previously was that companies should want to make money, because, besides money being generally a good thing (I think?), it’s the right way not to be distracted. Admittedly, it’s a bit roundabout. Ideally, you’d make money by staying focused, as opposed to staying centered on wanting to make money, but it’s hard to make money. Why not stay focused and see what happens?

OK, I am obviously being a bit silly here, but my point is that most companies fail at staying focused so bad that you could really extract a ton of profits in any industry by just keeping your eyes on the prize. You could scavenge through the academic literature here, but the conventional wisdom does provide a shortcut: do a few things and do them well and you shall be rewarded handsomely.

Treading water is bad, argues Will Larson

I am bringing all this up, because, every day, I am shocked at how bad our tools at the modern workplace are at encouraging and fostering this. So much work is spent treading water, as opposed to moving forward. We forward emails ad nauseam, switch from tab to tab to tab, move from one channel to another, in a futile attempt to get some work done, but The Work never gets done. Obviously, we take a step forward, and some things get done, but it’s hard to shrug away the feeling that we could have done a lot more with a lot less, if we were a tiny bit more focused.

But how does a company strategy relate to people staying unfocused at work?

Everything is Seating Charts

One of the more fun Matt Levine tropes is that “Everything is seating charts.” It’s obviously wrong, but if you worked at any big firm long enough, you know it is also correct. The wisdom it carries is just not that where you sit matters, which it obviously does as anyone who’s been asked to sit by the toilets would attest. Still, for most organizations, bureaucracy is a much, much stronger force of nature than strategy. The corollary of “all industries look alike in terms of profits” is that in most companies, how people work is way more important than what they do.

As much as you can try to shove a strategy down people’s throats, what happens in the field is more determined by the day to day operations of the working class. If your people in the trenches are not focused, neither are your operations. And if your operations aren’t focused, your strategy doesn’t matter one bit. Culture may eat strategy for breakfast, but bureaucracy washes it all down like a wine and steak dinner.

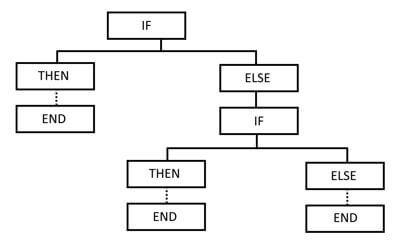

It’s hard to shake off the feeling that we are so far away from where we can be at a modern workplace. For example, Kevin Kwok’s piece on how Slack is really an “else statement” hints at the problem of how Slack, which is really only good at capturing what has fallen through the cracks, grows to become the work itself. Even if you have 5 people who need to send you messages every 2 hours, the mean time between two interruptions would be 24 minutes. This would be untenable in any information based industry, yet, we seem to be OK with it because we think that is work.

Feeling the Slack

Slack is work, and interruptions are work, but it’s not The Work. If Slack is the ultimate else statement, every branch is one step away from the goal. Every tiny bit of deviation is harmless by itself but compounded over time and across an organization, they add up to following an entire strategic goal.

This isn’t to say that you should avoid changing the trajectory of your company when you need to, or that any and all interruptions are bad. But as the (admittedly somewhat controversial) programming idiom goes, exceptions should be exceptional. If you find yourself deviating from your goal daily, maybe you do not have a goal to begin with and you are conceding ground to someone who does. If your entire day is spent being interrupted, and you find yourself at the end of the workday wondering what you’ve achieved day after day, the chances are good that you have not achieved anything. If you aren’t hearing the alarm bells by this point, be worried.

And this is not to say tools like Slack have no value. While the problematic behaviors Slack encourages, not just for work but culturally also, are well documented, it can be a useful tool. Ironically, this newsletter you are reading wouldn’t exist without it. While my co-host Ranjan and I met a couple of times in person (which is a story in itself), we communicate daily through Slack. Most of the Margin pieces start out as a banter on our Slack channel. Many companies, like my own employer who has several offices around the world, use Slack to get work (and The Work) done.

Alas, the room for improvement remains. As work gets modernized, it’s tempting to use the latest and greatest to get more work done. Yet, the key difference between doing work and doing The Work remains elusive for many organizations. Establishing a goal is hard enough, and staying focused on it is harder. And make no mistake, merely holding on to the wheel to go straight is work on itself too. It requires active maintenance, be it culling, or fostering a culture, or rather a bureaucracy, a way of working, that lends itself to staying focused from top to bottom. It does, however, pays dividends to do so.